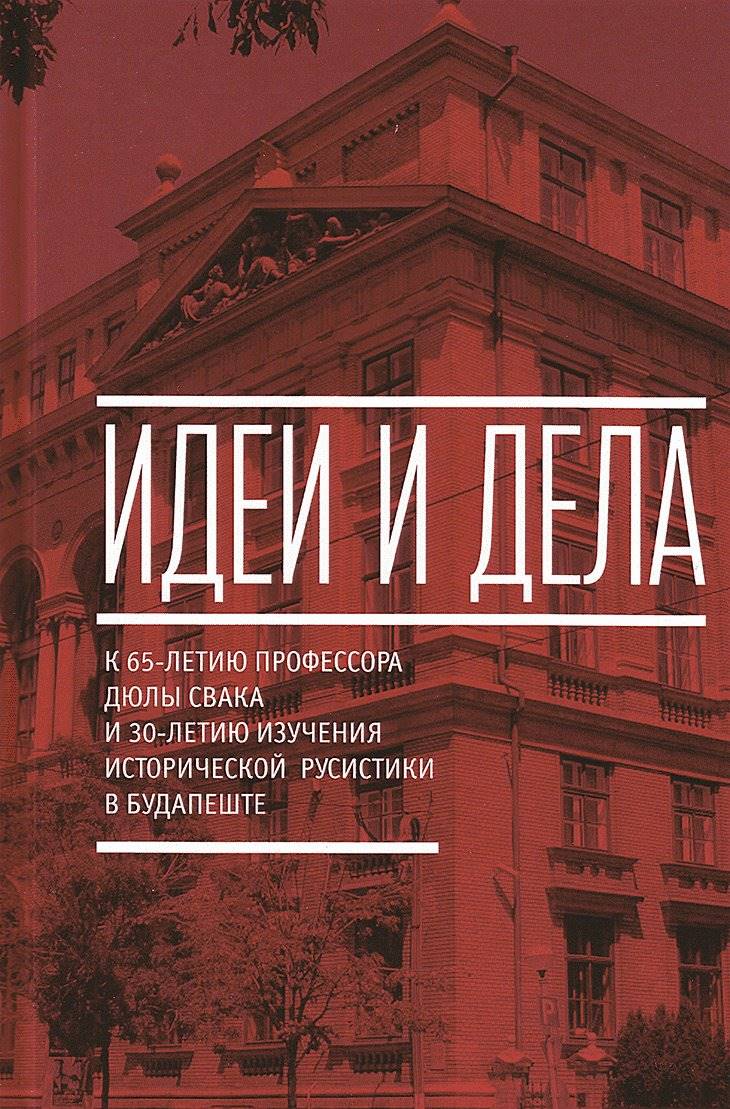

“It became clear in no time that an association pursuing academic goals cannot operate as an NGO run by volunteers. Research is a costly enterprise, and the Hungarian capital was not eager to give us a helping hand (not to mention its Russian counterpart). There were complications at the Faculty as well. At that time, Károly Manherz was the dean and he decided to put in order the Faculty that survived the years of the regime change in a run-down state. To be honest, our institute was the odd one out: we were inside physically, but we were outsiders from an administrative point of view. Therefore, the dean proposed to make us into a new organisational unit that answered directly to him, in the form of a ‘centre’, as it was fashionably called then. All this sounded wonderful, but to make it into reality, one thing was missing: funding.

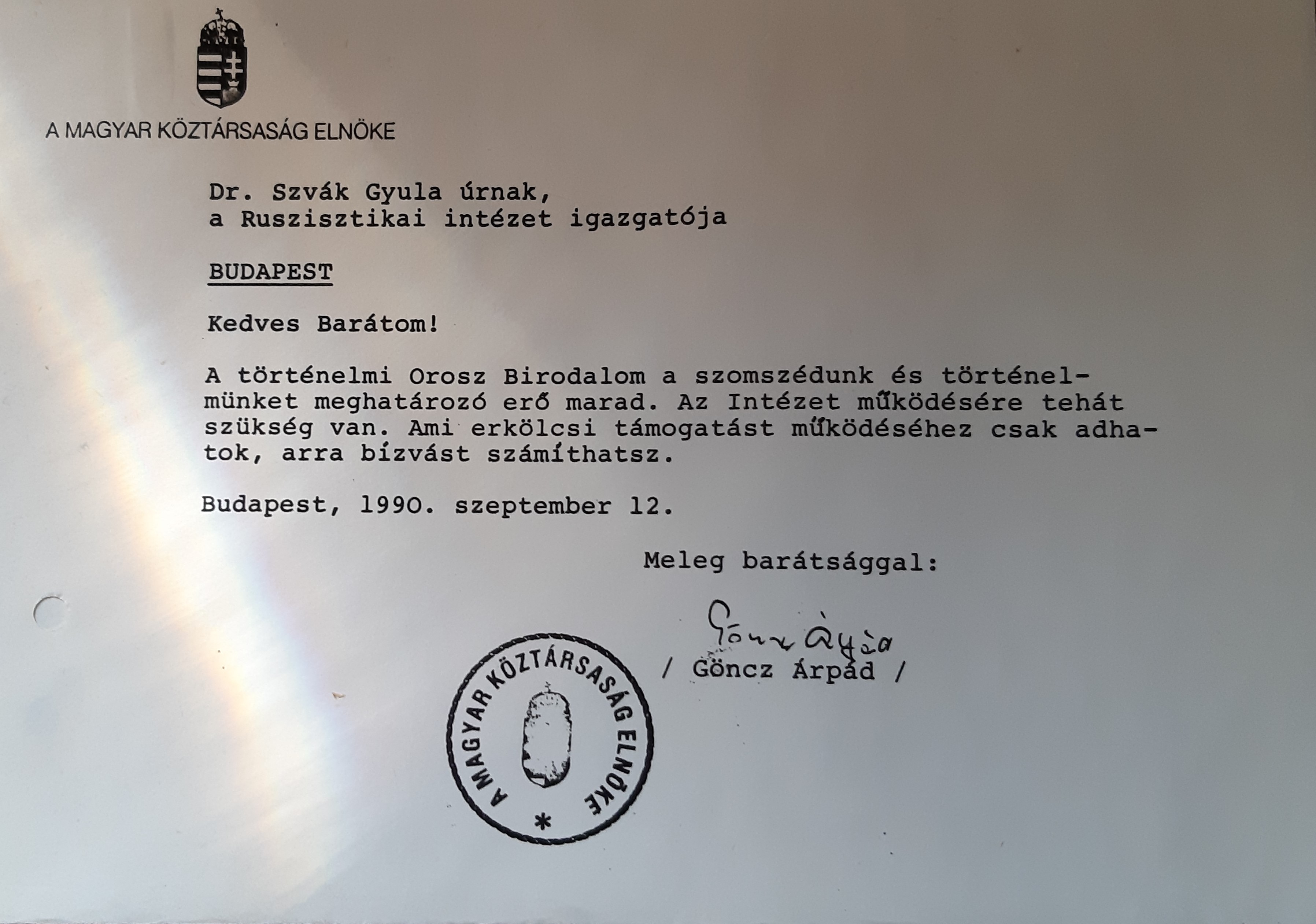

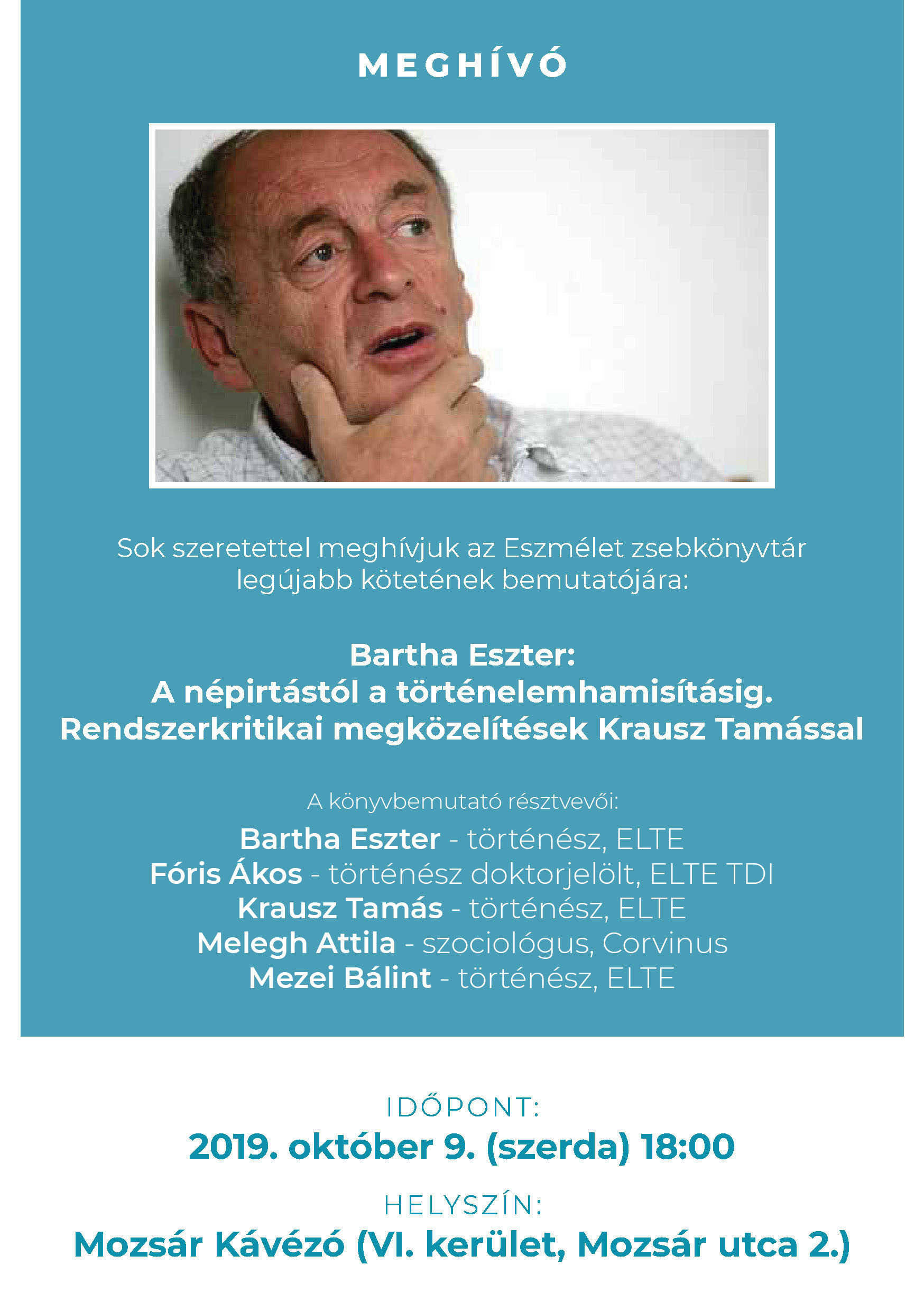

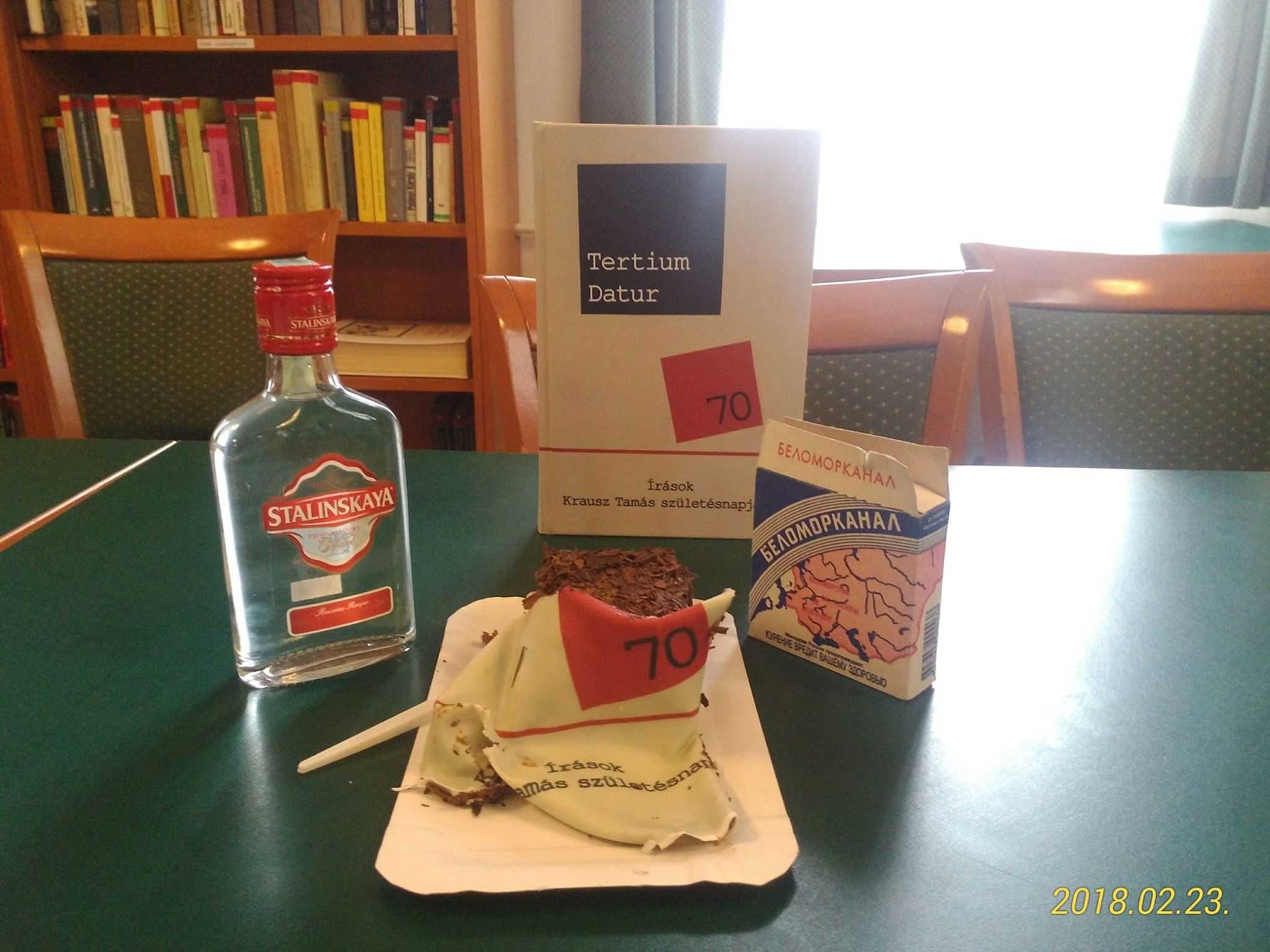

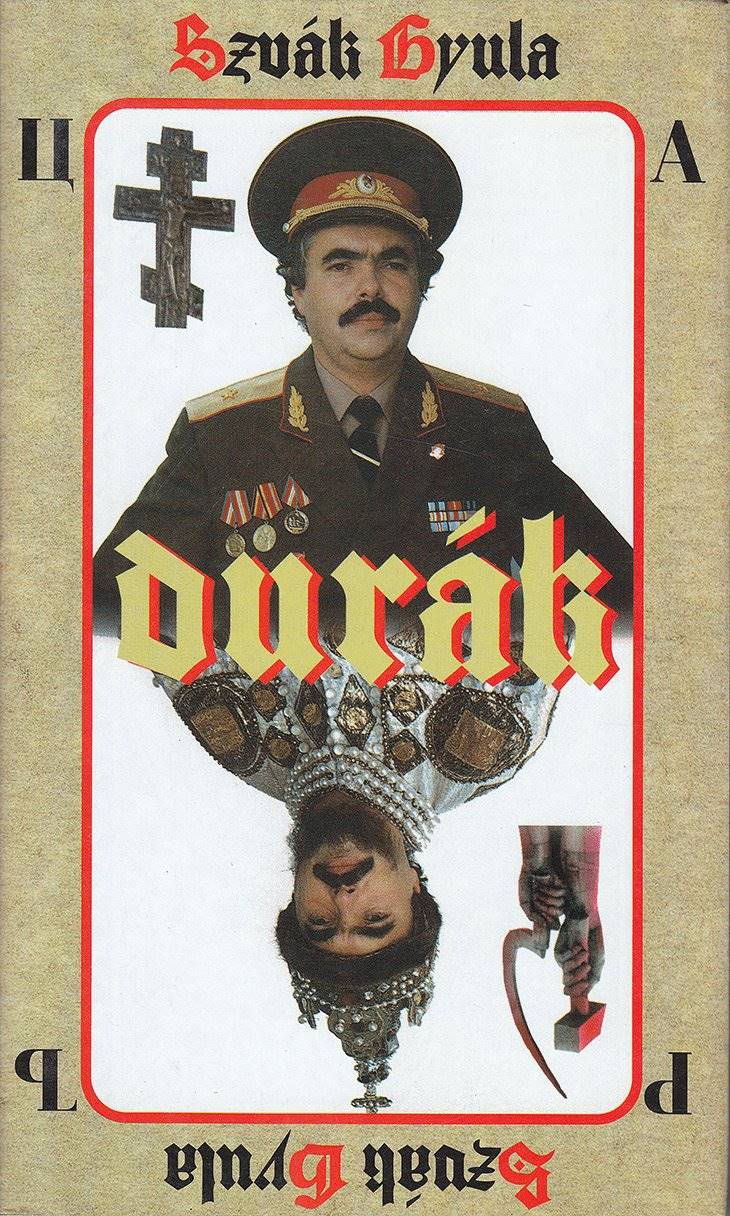

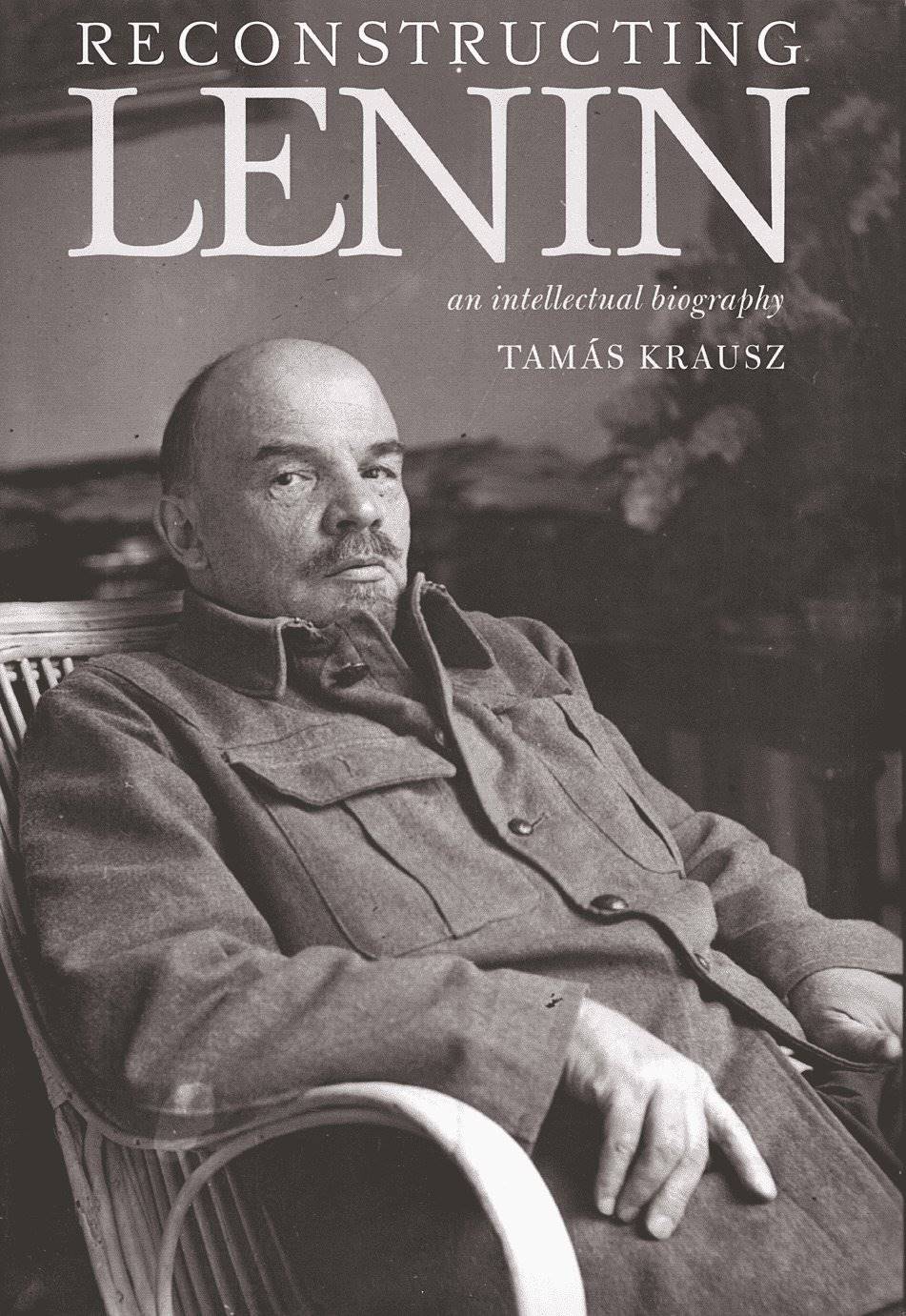

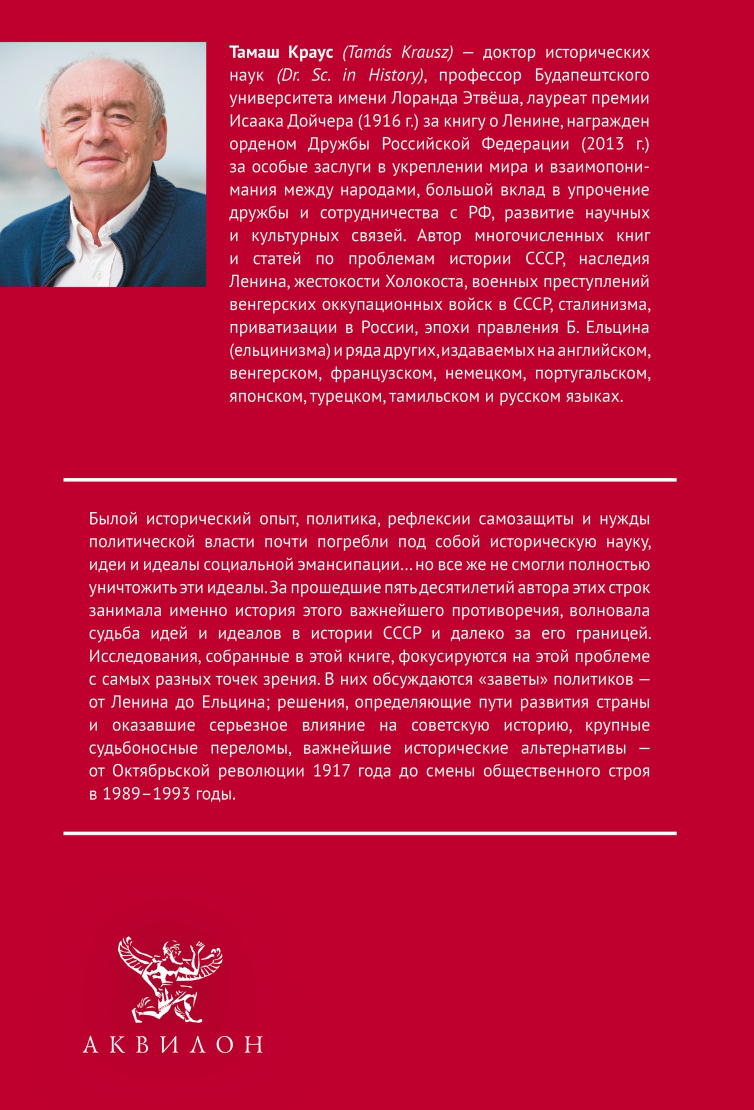

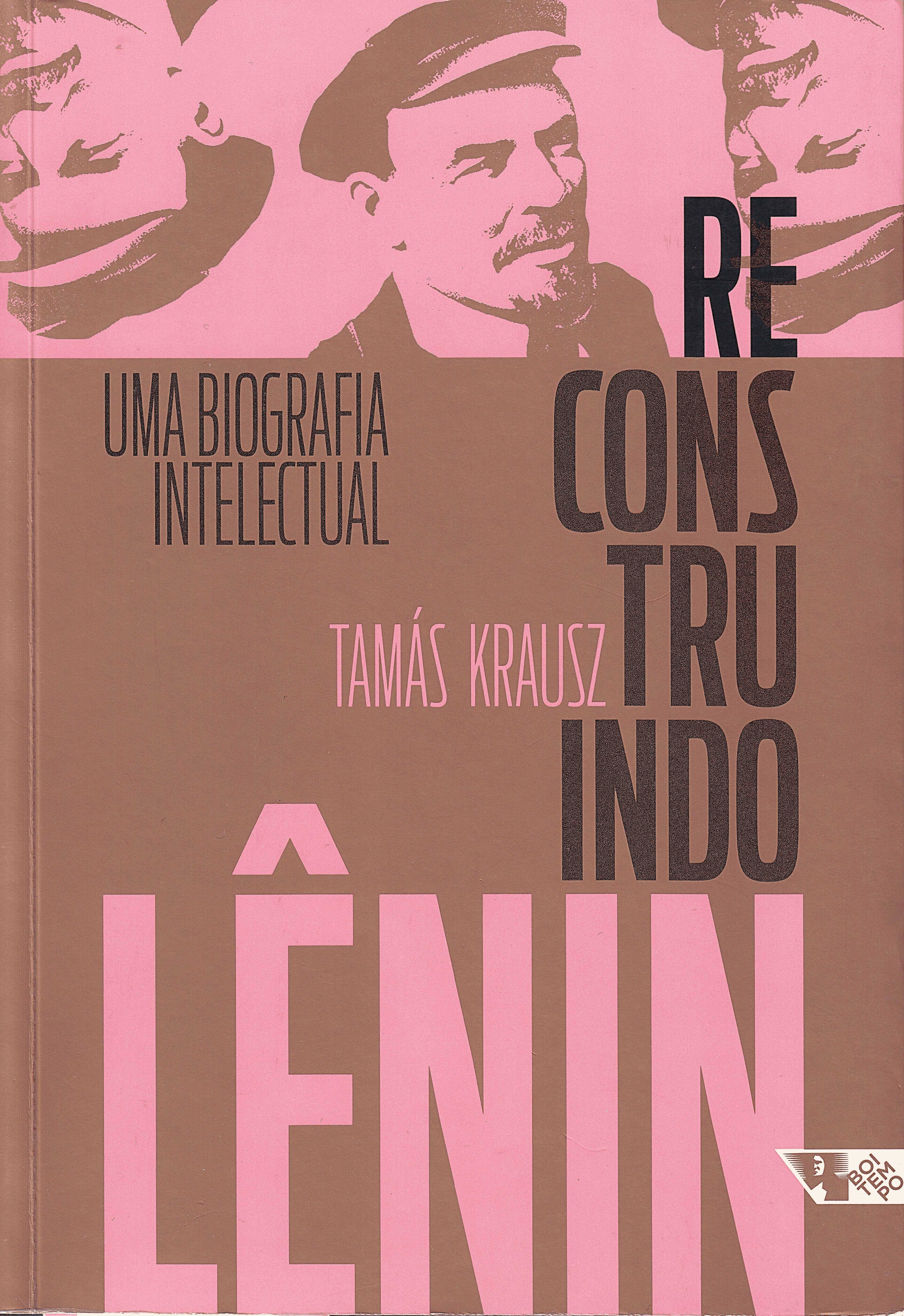

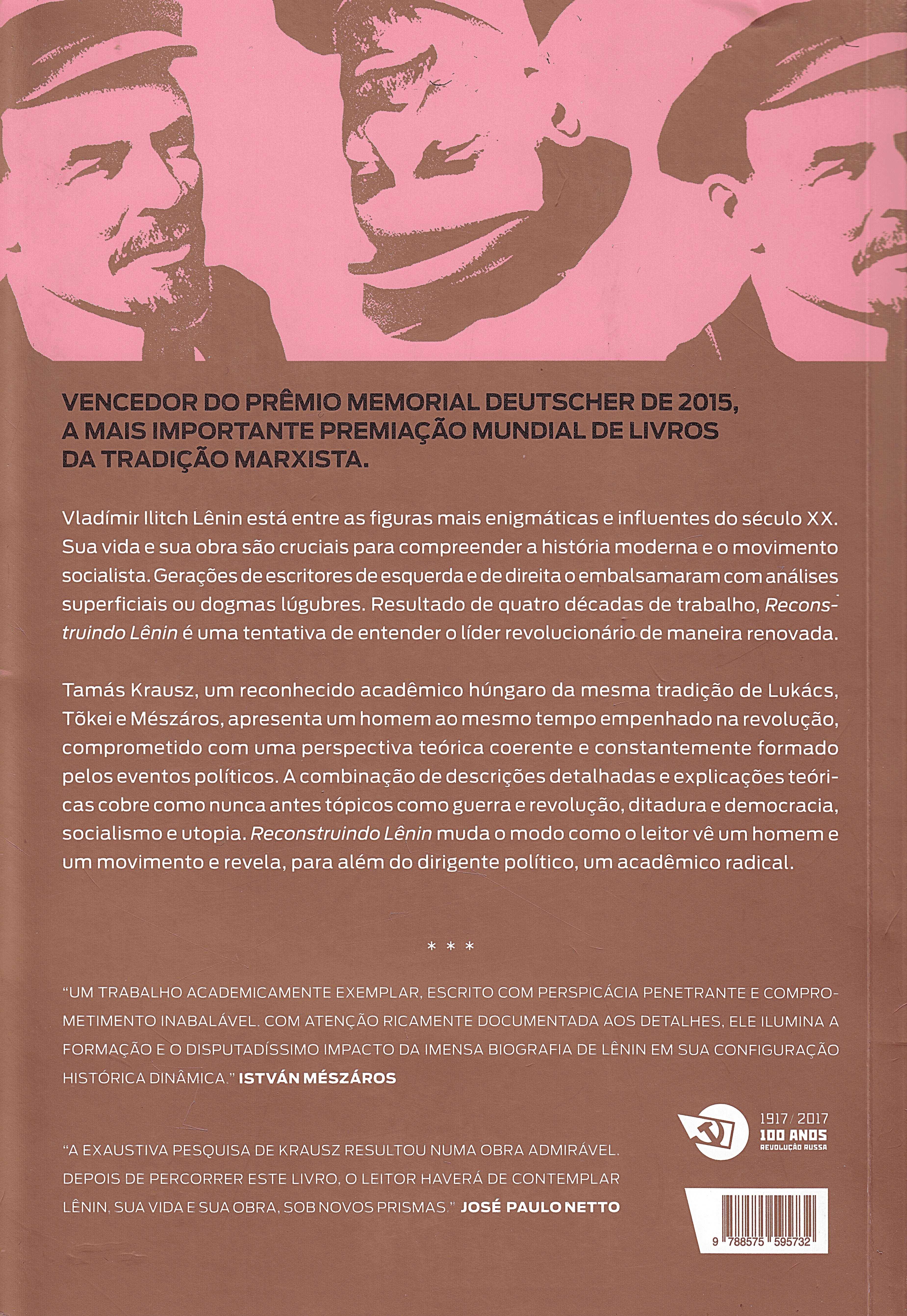

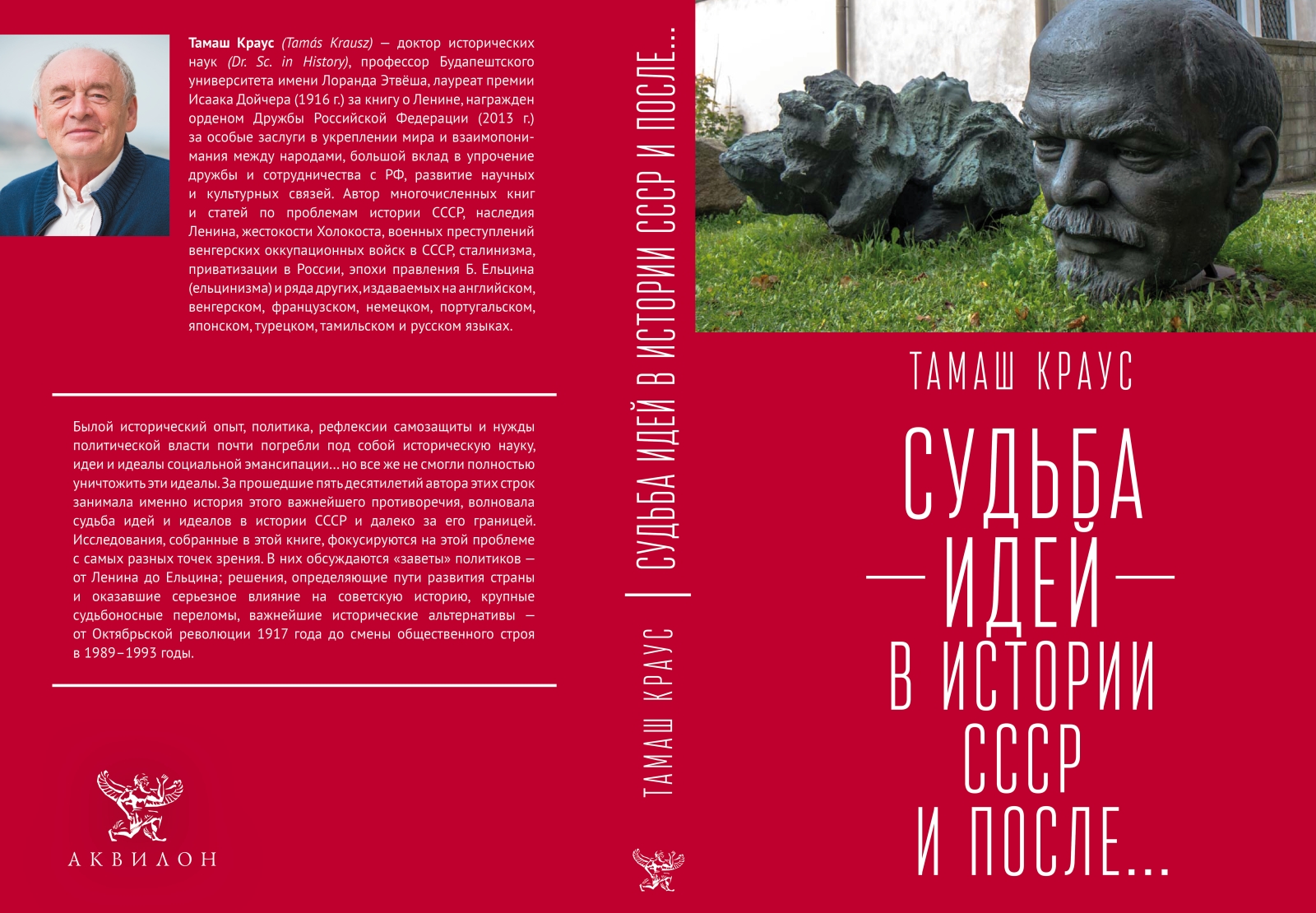

It was the Ministry that came to help us in the end, as it provided the Eötvös Loránd University with one full-time and one half-time salaried position. That’s how I became the head of the centre, and Ildi Lehr a single-person secretariat. In fact, the Centre for Russian Studies came into being, and has operated to this very day, through my friendship with Tamás Krausz (and our ‘partnership in crime’). I wouldn’t say it was a premature birth, but the centre had, beyond doubt, some handicap.

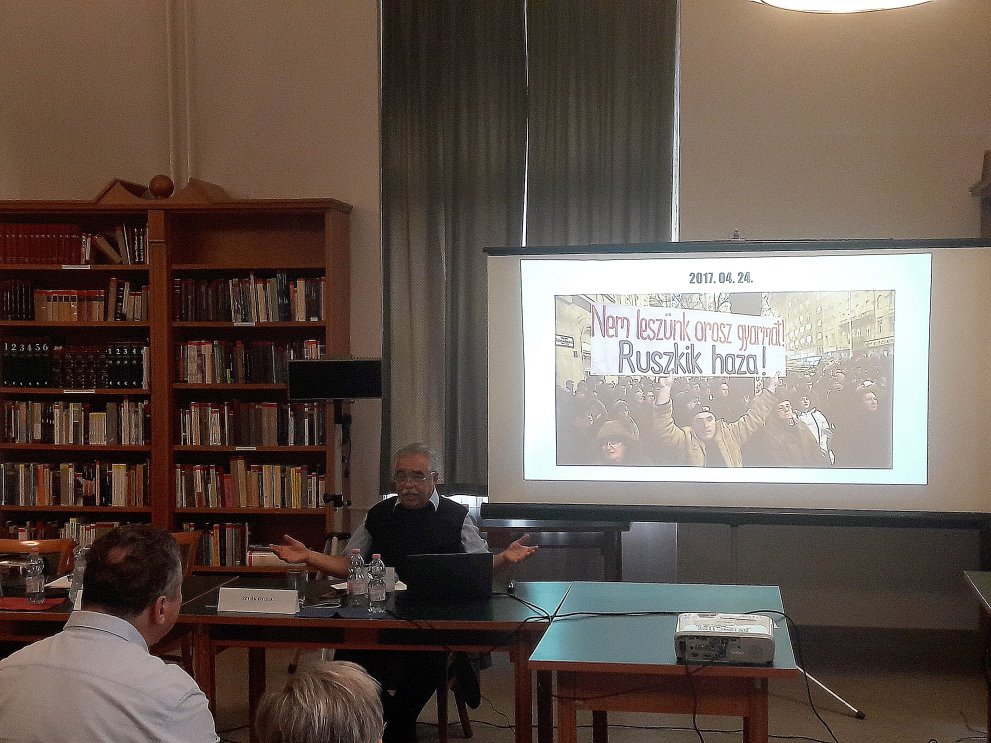

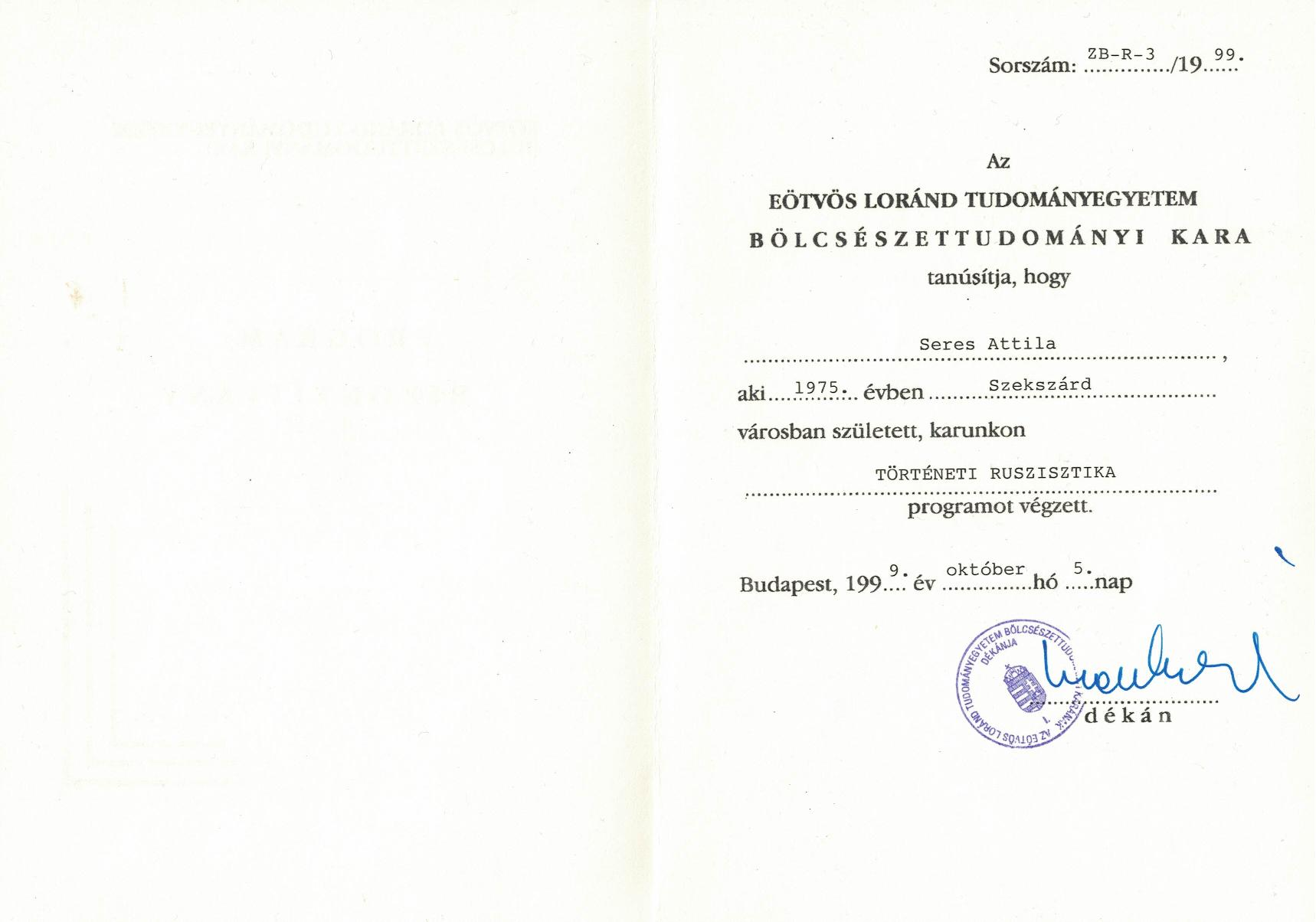

First of all, our name. In 1989, the Department of Russian Language and Literature still used the name Department of Russian Studies, and so we chose a name that distinguished us from them. [In Hungarian, the Department was called Orosz Tanszék, while the centre’s name was Ruszisztikai Központ.] In the period of the regime change, the Department of Russian Studies was renamed Department of Eastern Slavic and Baltic Language and Literature, but we kept this strange Hungarian name, Ruszisztikai Központ, hardly understood by anyone except the initiated members of our circle. Moreover, our special programme soon to be launched was christened Historical Russistics and Modern Sovietology, in order to differentiate between educational competences. Ten courses were launched, and we taught for free as volunteers, simply because we had a name but no salaried teaching positions. No wonder that people jealous of us were not particularly numerous. Most people don’t like working for free, especially not if they have to sail against adverse winds, like scholars of Russian studies had to after 1989.

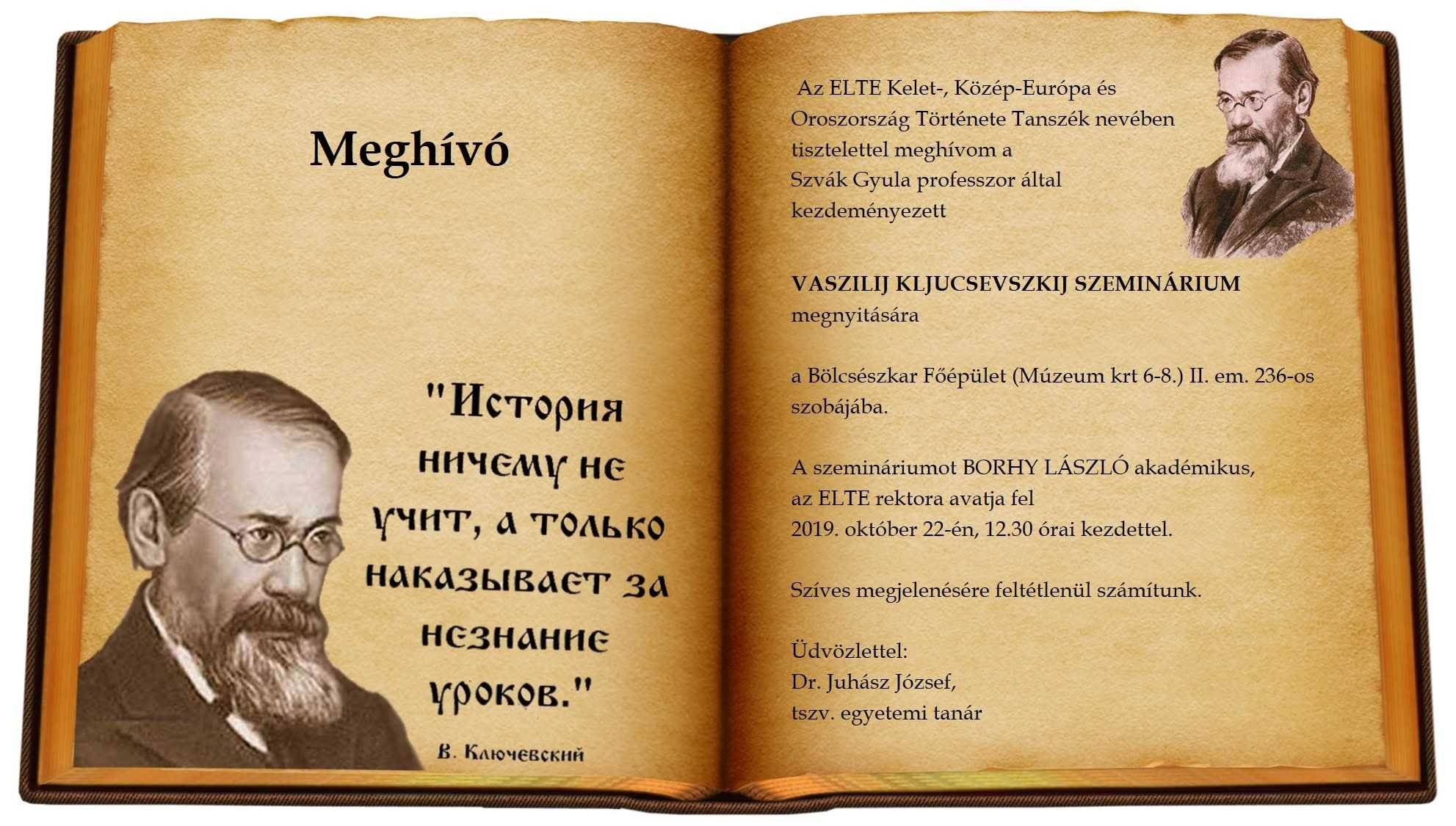

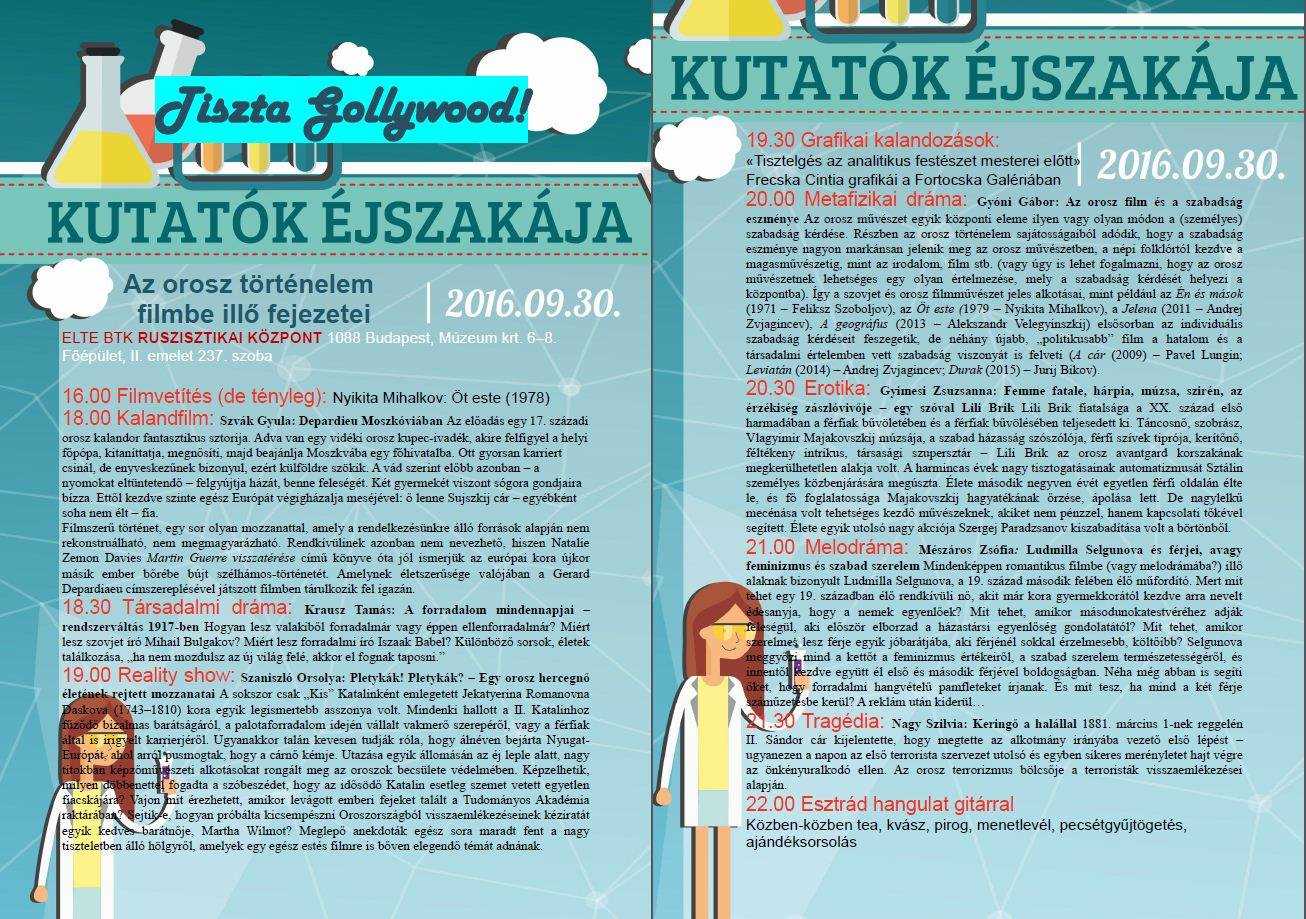

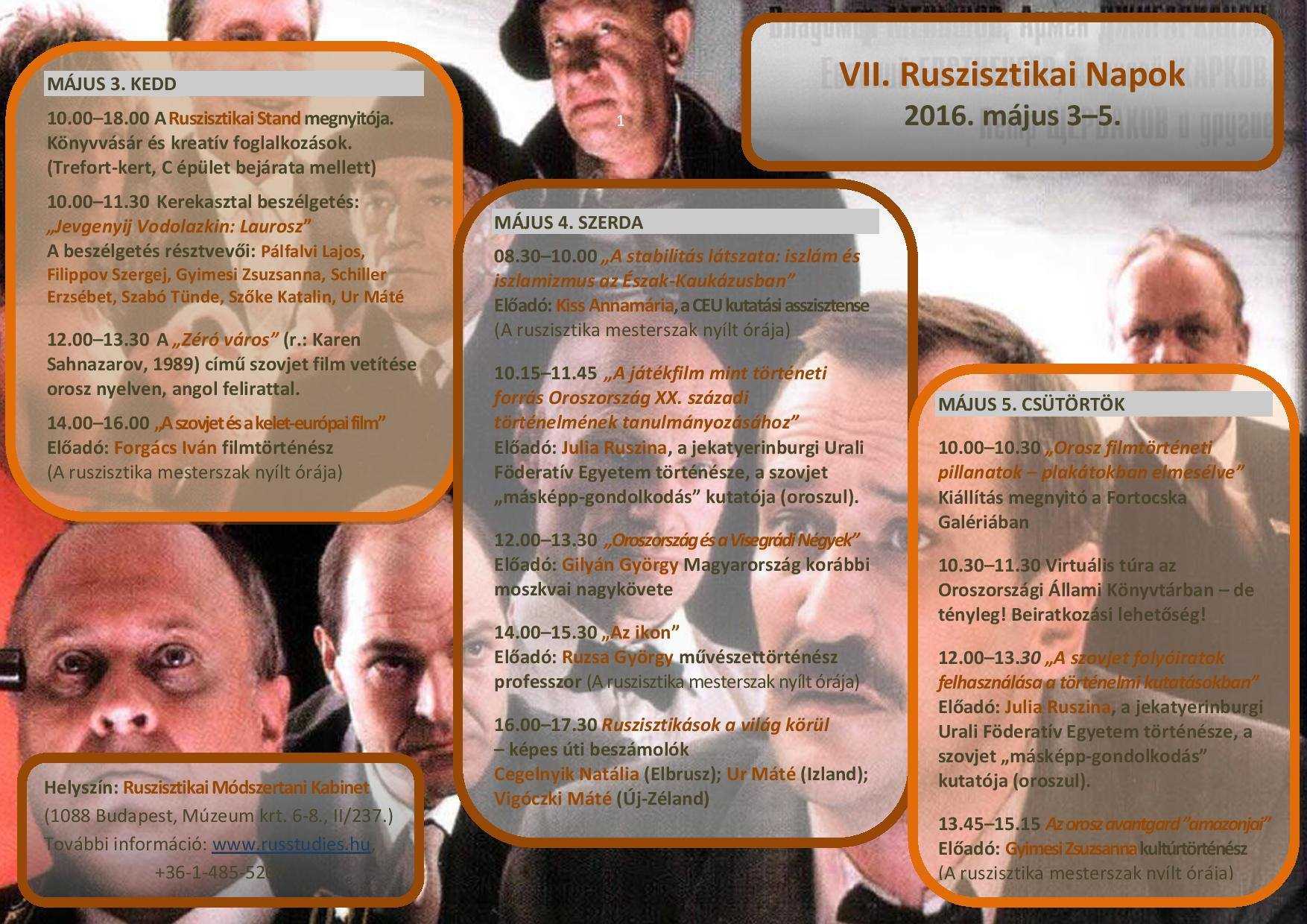

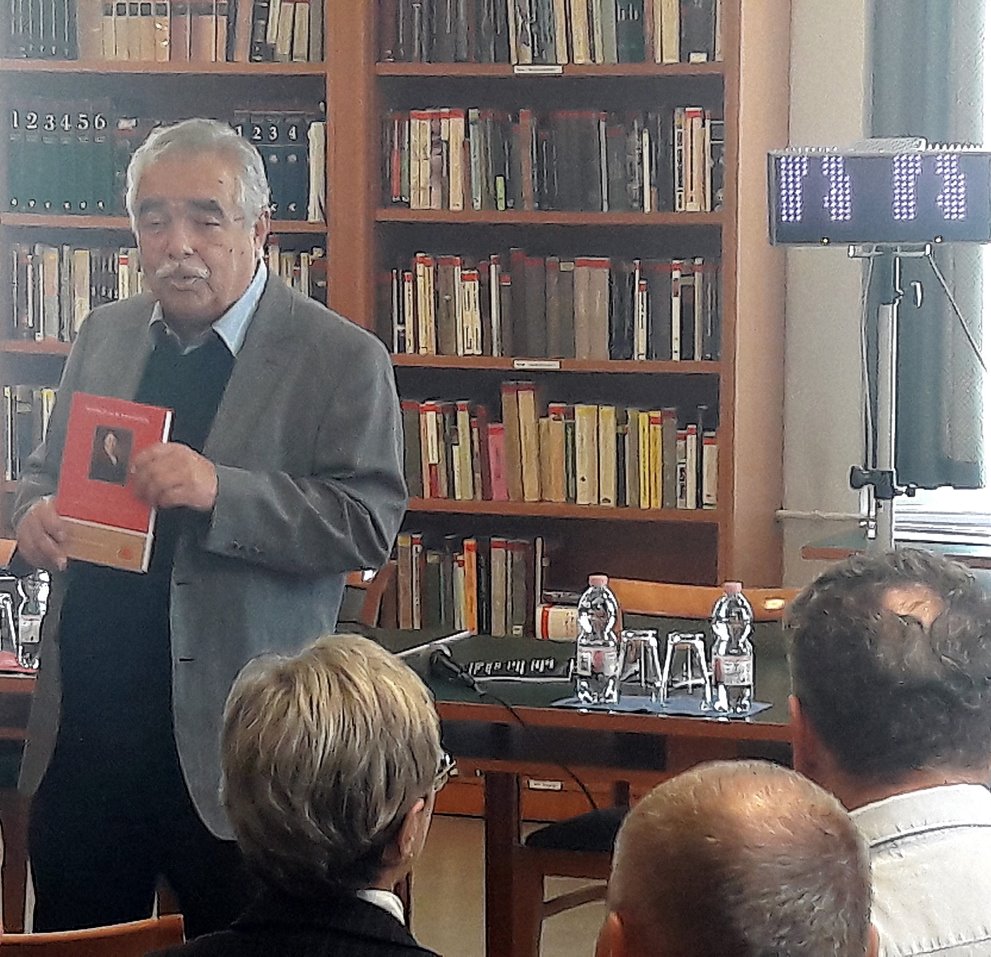

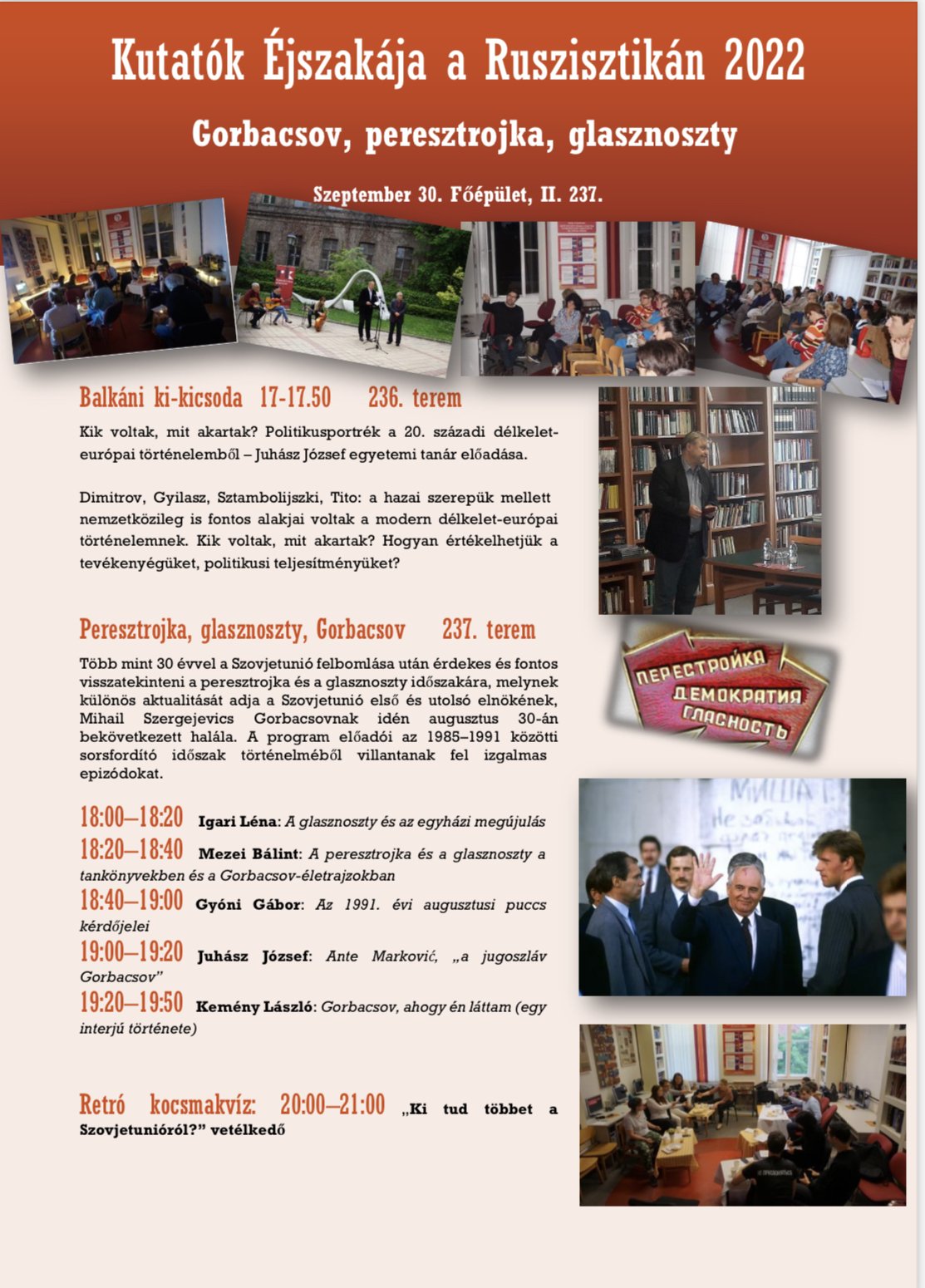

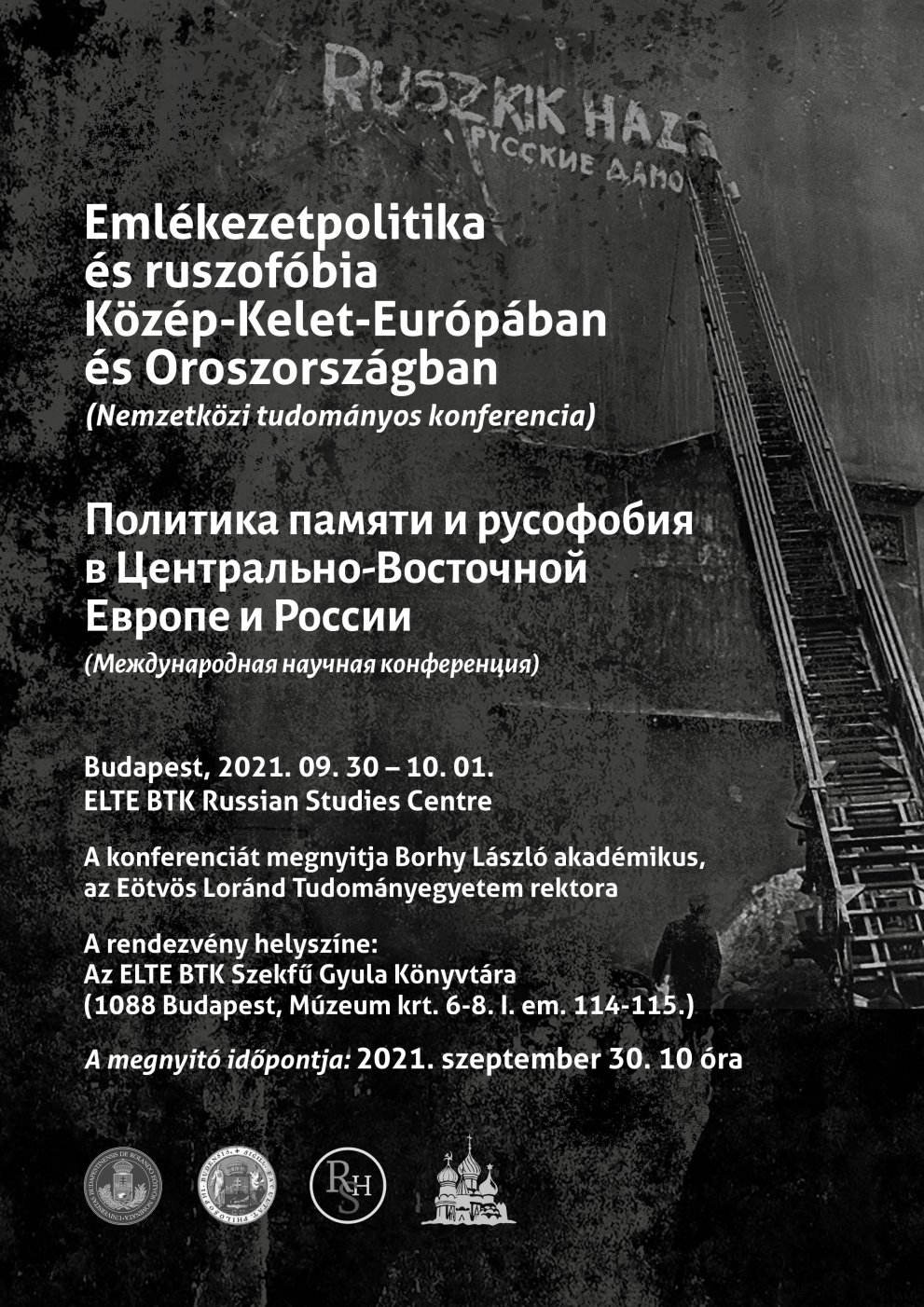

The breakthrough came in 1998, when we organised our first international conference (or rather, symposium). Since then, this assembly has been held every second year. Scholars of international distinction came to participate, crossing the Atlantic; the doyen of international Russian studies, Nicholas V. Riasanovsky, was among the distinguished guests, and other globally acknowledged scholars followed in his footsteps. We owe thanks to the connection network of Ruslan Grigorievich Skrynnikov, which helped us immensely during organisation. Dmitry Sergeyevich Likhachov also supported us indirectly, as I was able to meet Professor Riasanovsky at Berkeley thanks to a reference from him. As I look back, it seems that the Centre for Russian Studies gained a foothold at an international level first. No one is a prophet in his own land, and this also applies to scholars of Russian studies.

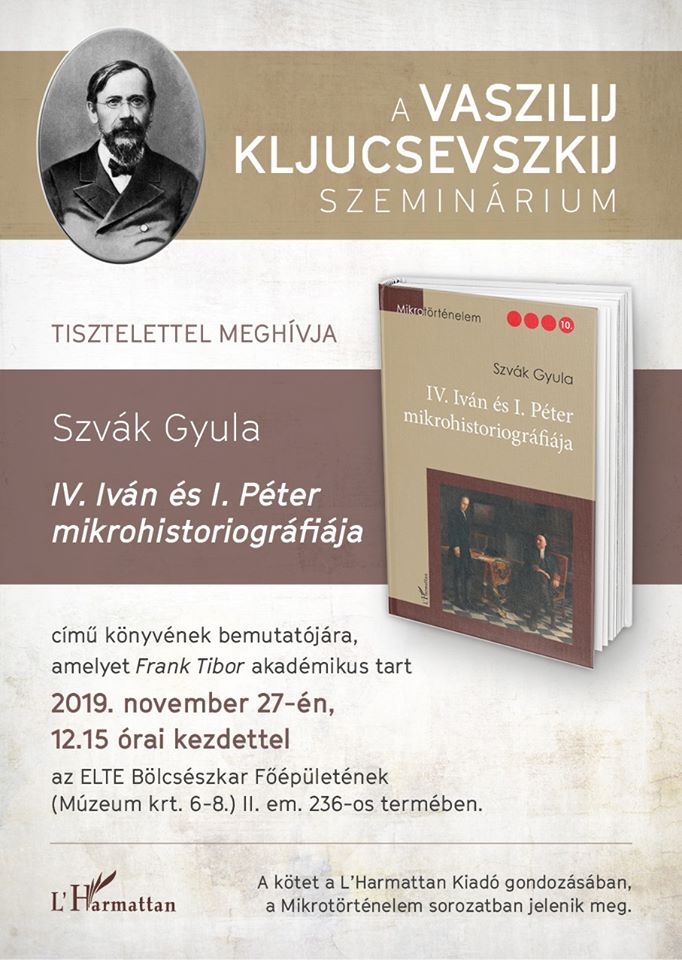

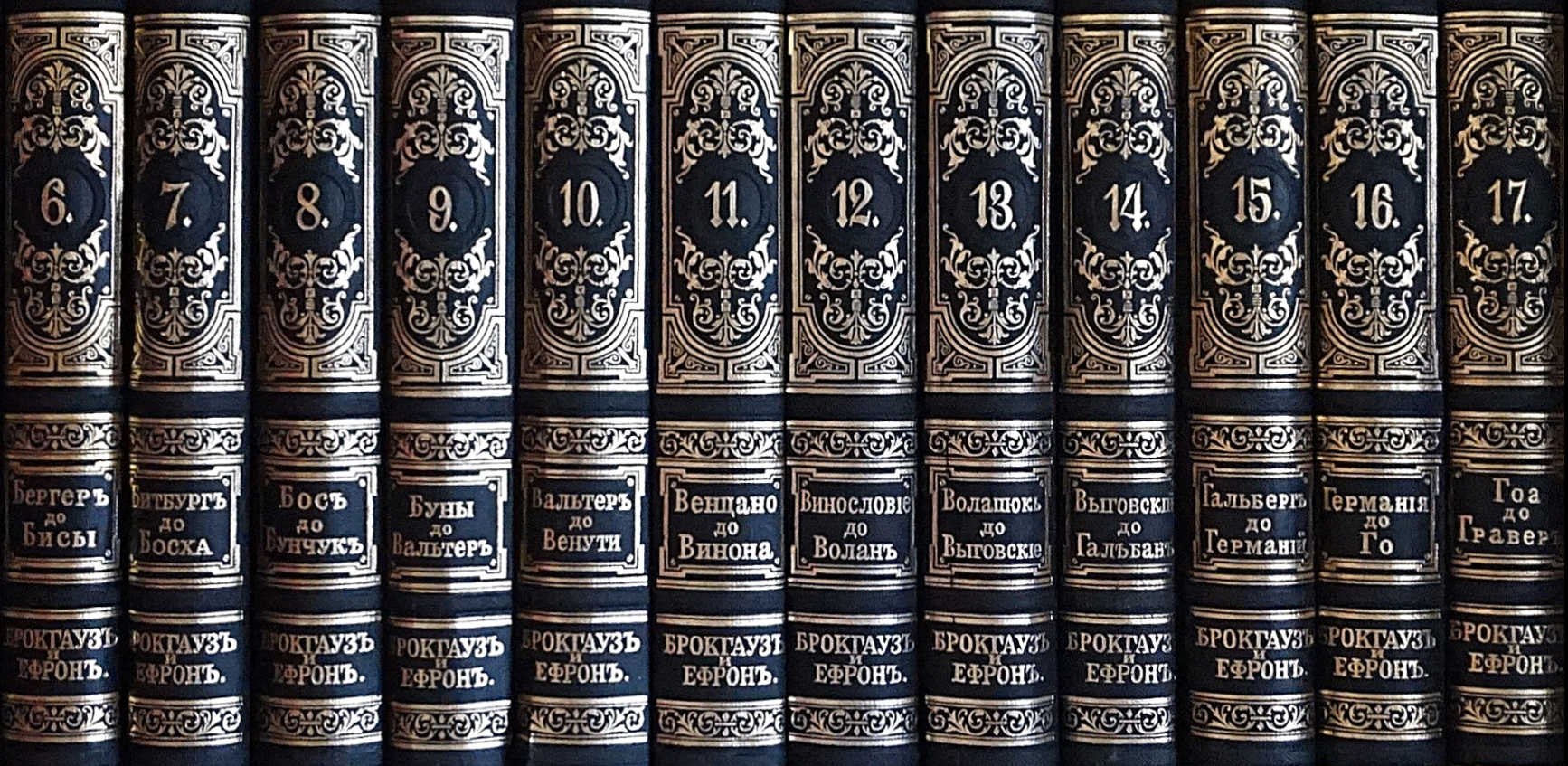

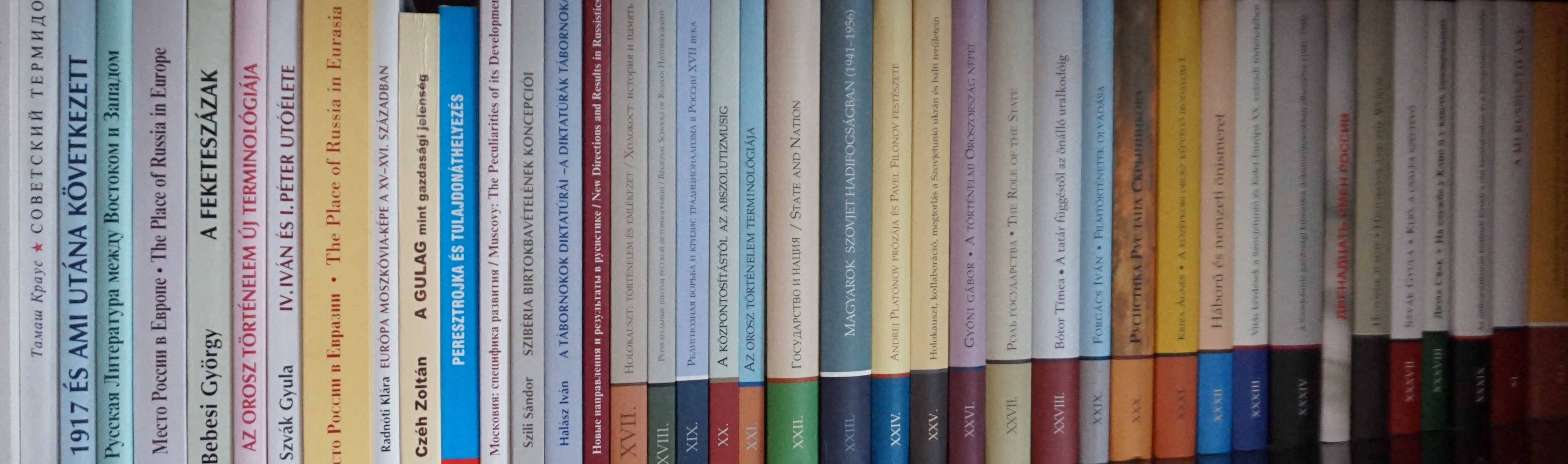

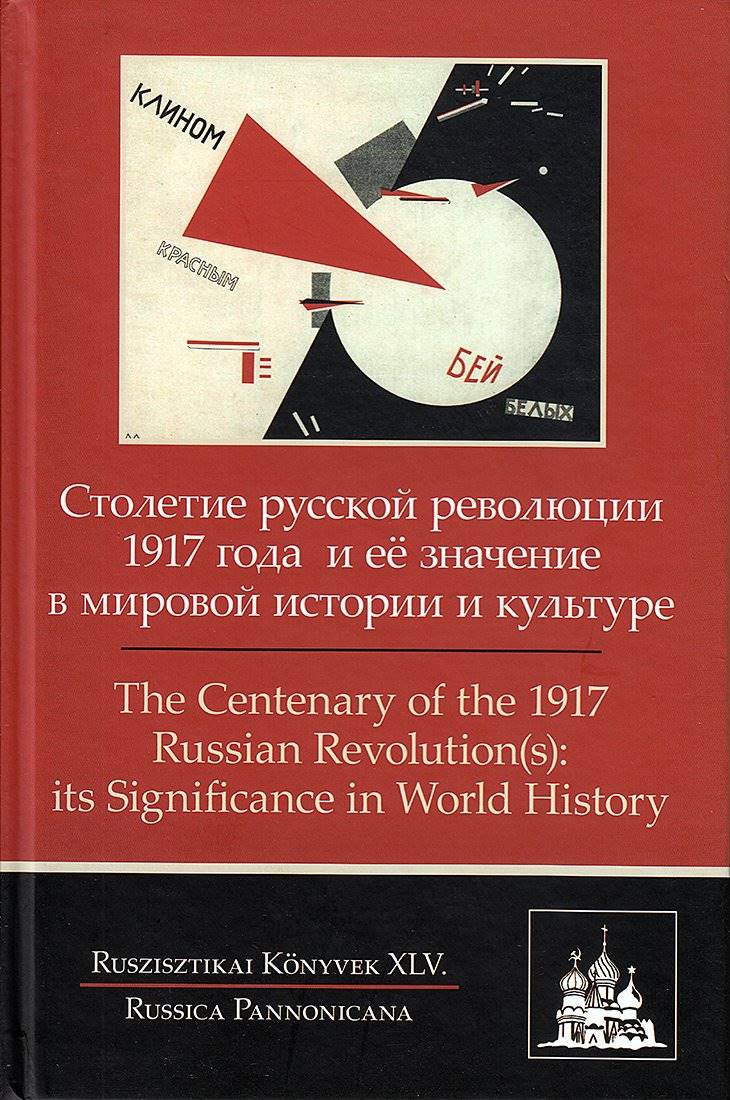

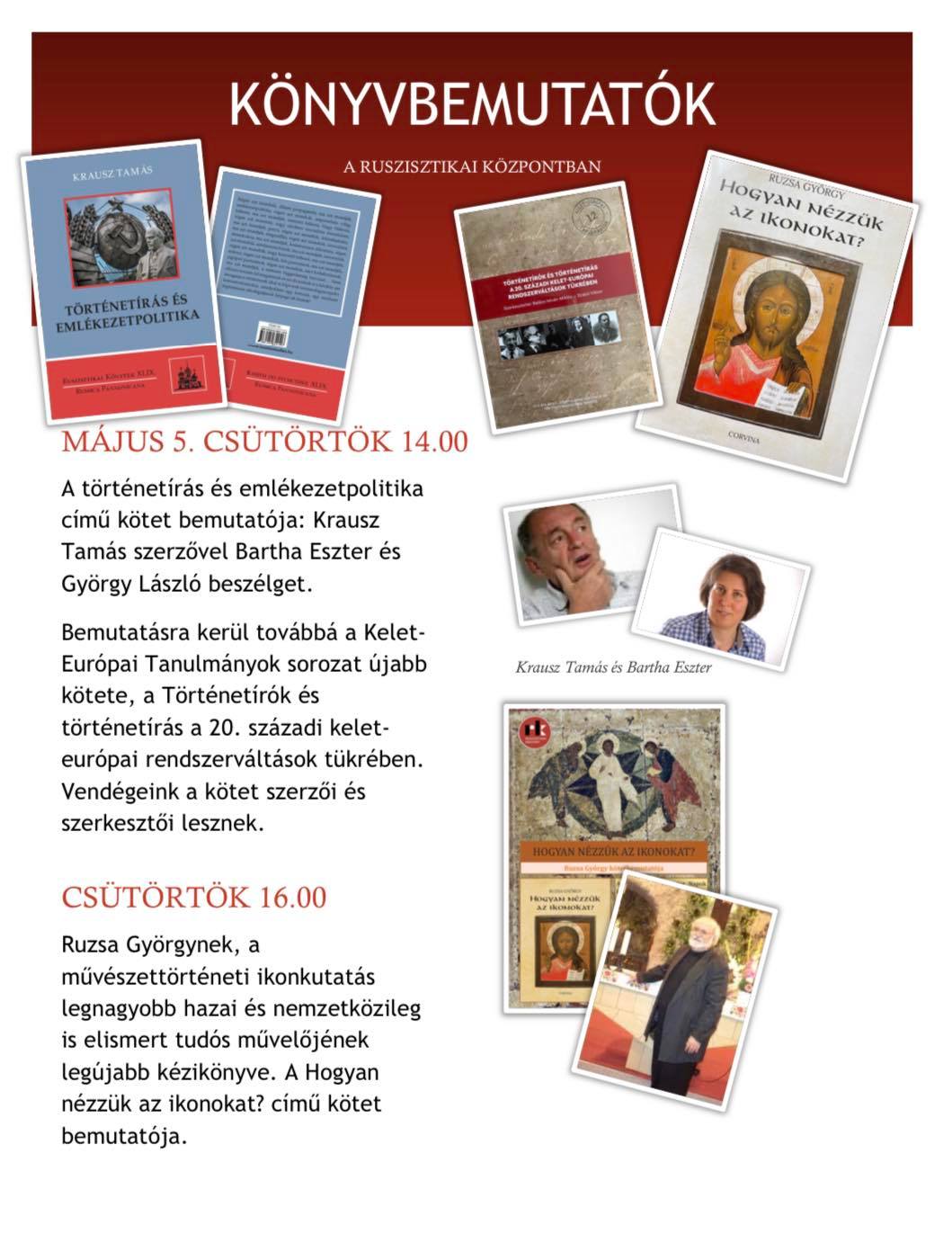

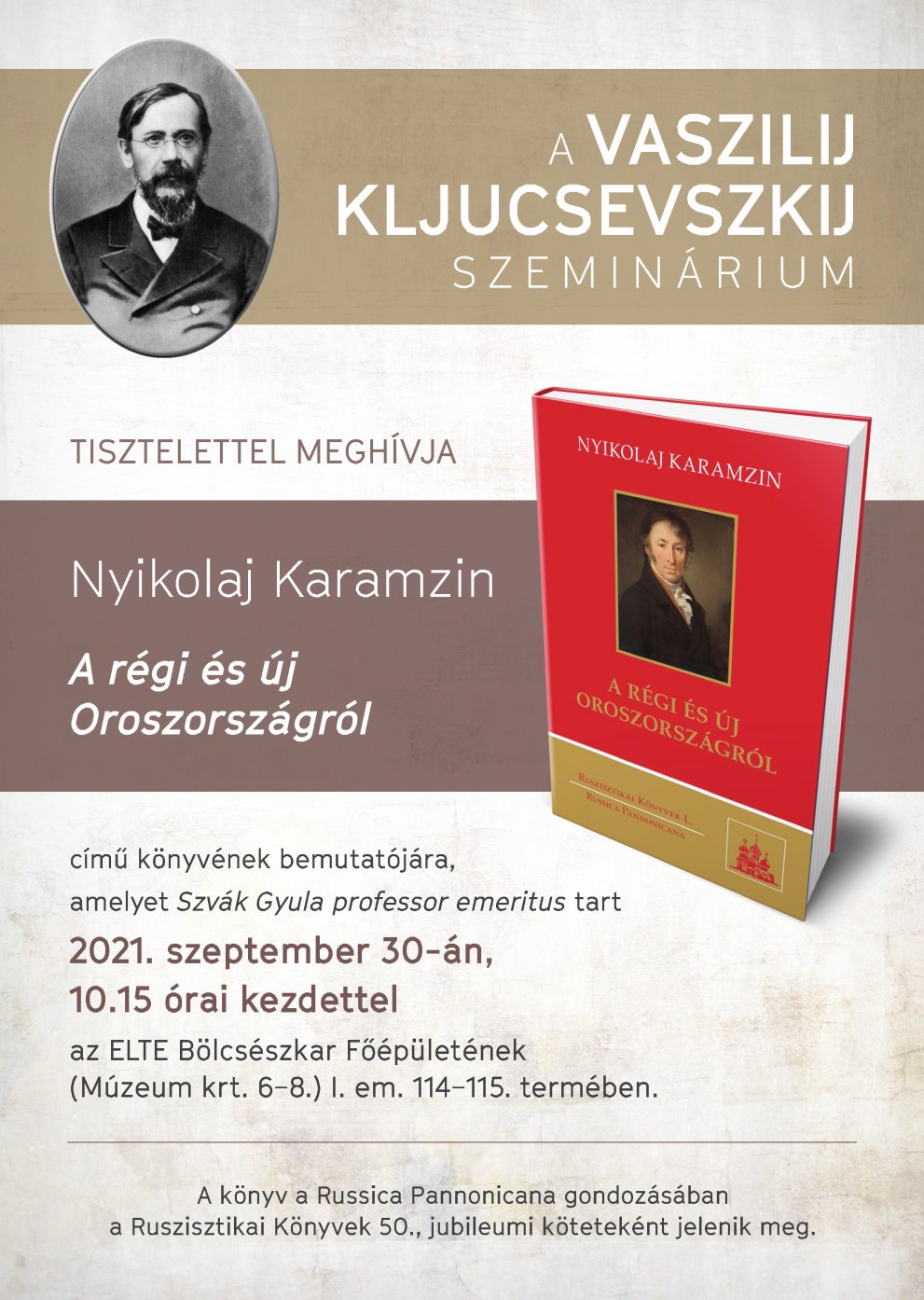

Creating the Research Group for Historical Russistics in 2002, based on the Centre itself and embedded in the Network of Research Sites of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, was the next major step. First there were only five, later 15 members, and a few additional employment positions, in cooperation with colleagues in Pécs. In these years, this research group provided funding for our extra-curricular activities, such as publishing books. The number of publications in the series Books on Russistics grew steadily in the early 2000s, partly due to this support.

A series of events titled ‘Hungarian-Russian Cultural Seasons’, as well as a general and spectacular improvement of Hungarian-Russian relations in the middle of the decade brought vital changes for the Centre. In 2006, the Foundation for Russian Language and Culture was established.”

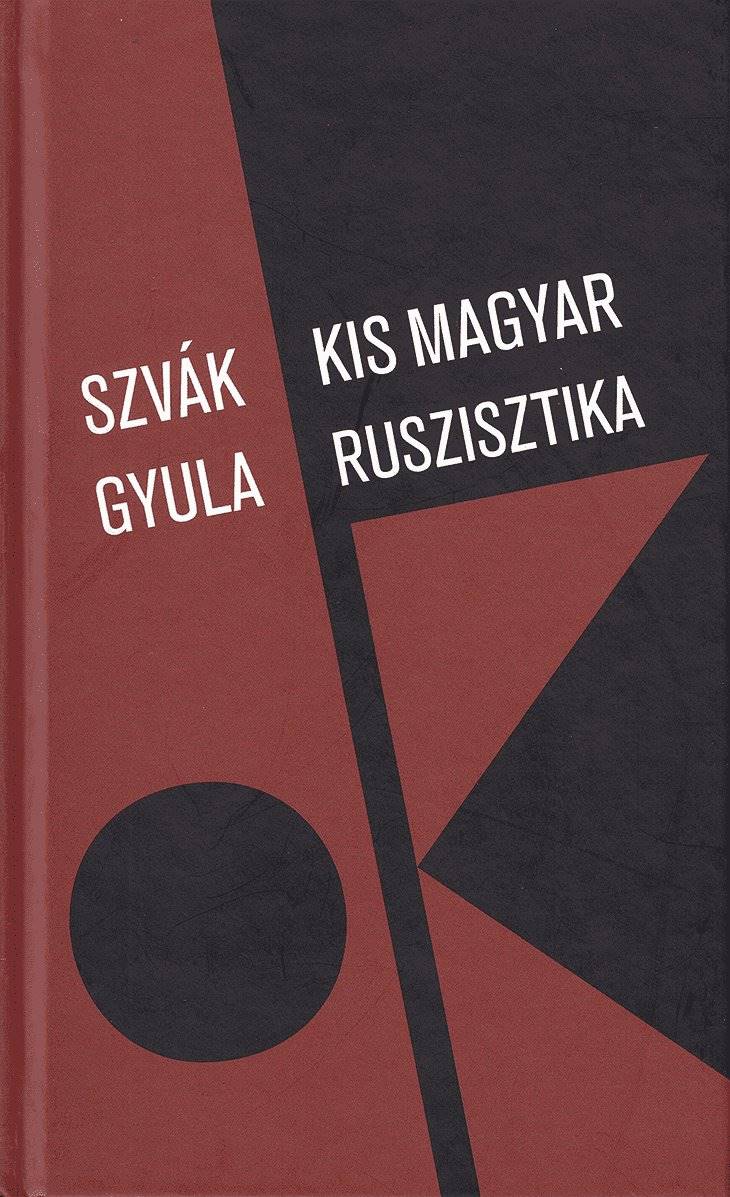

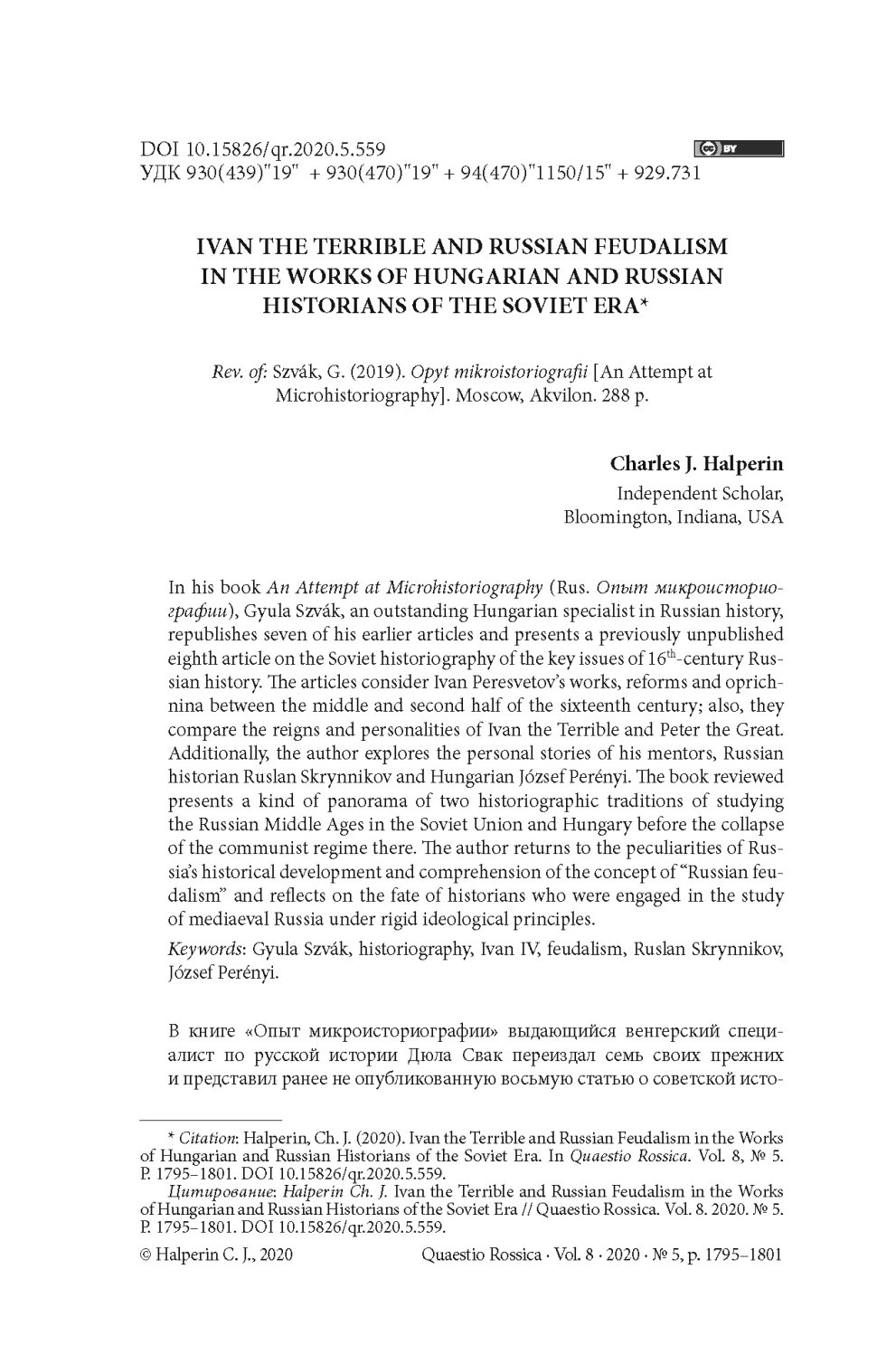

(Excerpts from Gyula Szvák, Kis magyar ruszisztika. Russica Pannonicana (2011), pp. 112–114)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)